The Buriganga River flows through southwestern Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, with traffic not too much different than the rest of the city. Small wooden porter boats dodge hulking barges and foghorns blare as children swim off concrete banks. The waters are dark and murky, and the city’s trash washes up on its beaches.

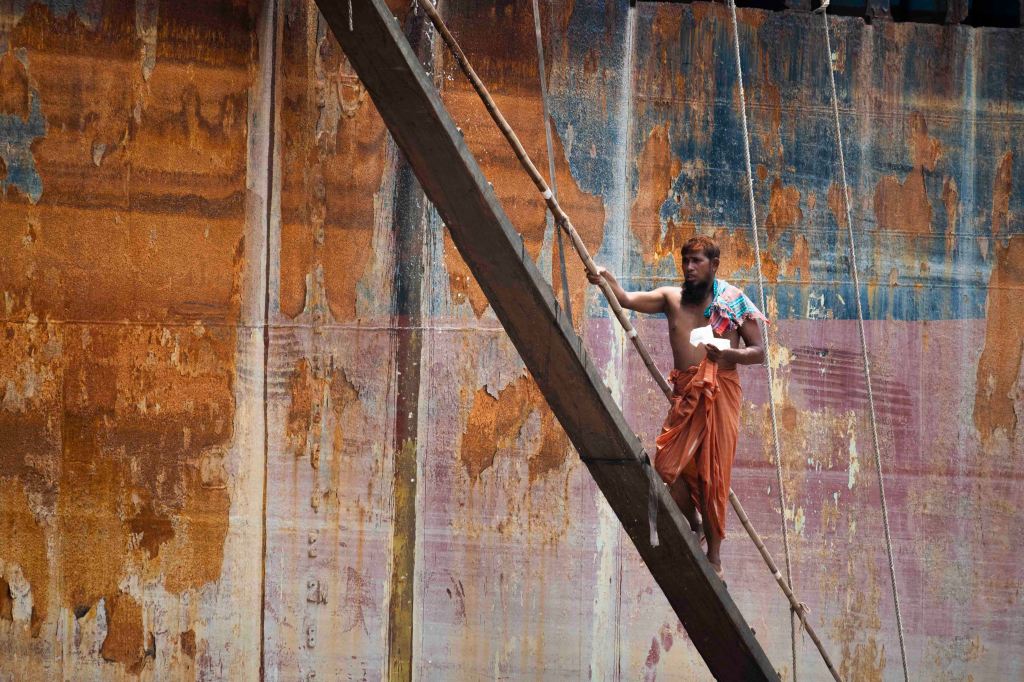

The Keraniganj area of the river is dotted by shipyards, squeezed between houses, shops and mosques. Workers haul scrap steel off ships, make repairs and repaint boats. The Friday Muslim prayer echoes between rusted hulks. Today would be a weekend for most.

Twenty six-year-old Miraz Hossain has been working the yards for 22 years. When he was 4, his father died of electric shock and Hossain was forced to provide for his mother by himself.

“All my siblings were married off or had found work and left on their own,” Hossain said. “Nobody stays in touch anymore. I haven’t seen any of them in quite a while.”

The shipyards are dangerous – workers haul heavy pieces of rusted metal up and down bamboo ladders, sparks hit the faces of unmasked welders. Personal protective equipment is often limited to loose pants and sandals. Ships are beached by 50-plus men with ropes, no winches, cranes or heavy machinery in sight.

When he was 8, Hossain suffered a serious injury to the right side of his head and his shoulder after being crushed by a massive piece of scrap metal while lending a hand to some of the haulers.

Some of the highest paid workers in the yard, haulers make anywhere from $150 to $175 USD per month. The company offered no support for his injury, and he was made to pay the medical bill by himself.

But he continued working at the yard, picking up other odd jobs if the daily pay could be better, or if he needed some brief change.

If the 100-degree heat of the open yards became unbearable, Hossain would find a cooler gig for the day, a common practice for wage laborers in Bangladesh. These floating laborers make up the country’s informal economy.

According to the International Labour Organization, this informal economy makes up 87% of Bangladesh’s workforce. On the other hand, Urban.org studies suggest between 3% and 40% for the United States.

Between his odd jobs, Hossain knew he needed to keep his steady employment at the shipyard. He was lucky.

“My friends would ask me for work, but I myself was struggling to find work,” he said. “How could I help them? Nobody gave work, we had to hold feet and beg for jobs.”

Hossian is still the sole provider for his family, now with a wife and two kids. He will continue work at the shipyard – to him, it is a privilege.

That’s a very insightful article

LikeLike